This is the beginning of my book Katahdin, Henry & Me. I am currently shopping for an agent to find it a home.

Prologue

I've always loved maps, especially the areas of parks and forests shaded green or brown. In my basement, I have a huge box stuffed full with the hundreds of maps and guidebooks I've accumulated over the years. Maps from every state except Hawaii. Many are outdated, but I can't bear to throw them out. Maps are guides to a world beyond the ken of Western civilization. I read that as a child Salmon Rushdie kissed any book he dropped on the floor; that's how I feel about maps. On a bookshelf, in my bedroom in Maine, are dozens of maps of New England: state parks, Maine reserved lands, topos, hiking maps of the White Mountains, National Parks, the Appalachian Trail, maps downloaded from the internet, maps ordered online. There are three maps of Baxter State Park alone, one worn and going soft at the edges.

Maps speak to my imagination. They tell me stories of mossy forests alive with moose and fishers and orange salamanders that glow in the gloamy leaf litter. As a child, maps were dearer to me than the illustrated Bible I received for first communion. In second grade I got sent to the principal's office for telling my teacher I didn't have to believe in God if I didn't want to. But I always believed in the wild places on maps.

I grew up in Greenhills, Ohio, a planned suburb of Cincinnati built during The Depression. The town was ringed by a “green belt” of woods that by the time I was born had become Winton Woods County Park. A block from my house, behind the high school, a well-worn trail led down through the woods to a pond. My friends and I lazed beside the pond with our bamboo cane poles fishing for blue gills with worms.

In the woods behind the elementary school, we caught crayfish in the warm muddy stream that tumbled through a shaley ravine. We hiked for miles and miles between creek and pond through the woods, bushwacking through the crinkly underbrush like a pack of feral dogs.

Even as an eight-year-old, I couldn't ignore the houses through the screen of trees, or the sound of traffic on Winton Road that penetrated into the wooded gullys we discovered. I brgn pouring over maps of the United States, looking for real wilderness.

When I was nine, my family took our first vacation; a camping trip to the Great Smoky Mountain National Park. We climbed Clingman's Dome and stood on the white concrete observation platform and gazed out over endless rows of hazy mountains. Luckily for me, my family took several camping trips each year, many to The Smokies. Visit after visit, the Smokies seemed less and less wild, more my mountainous backyard. I wanted even more wildness. Bigger blanks on the map.

Then a spot on a map of northern Maine in our family's road atlas sparked my imagination. Thoreau's North Woods: a place so wild that his deathbed words—Moose. Indians—recalled it. The place called to me repeatedly after that. I ran my finger along its edges in the family atlas, mispronouncing the exotic Indian place names under my breath. One day when I was ten or eleven I discovered a National Geographic coffee-table book on American wilderness at my grandparents' house. The book included a photograph of a waterfall in Baxter State Park. In my eyes the spruce forest loomed over and around the stream: dark, mysterious. I could get lost there, disappear into its indifferent embrace. Baxter State Park, the book explained, was a wilderness park. The living heart of that big blank spot on the map of Maine. When I closed my eyes, I could smell tree sap and rotting leaves. I heard the water crashing over broken granite.

I made sure that when my grandparents got older and downsized their living space, that I got that wilderness book. Now tattered and worn, it lives with the hundreds of maps in my house in the woods in Maine.

Section 1:

The Freezeout

July 2010

Day One: To Hudson Pond Lean-to (8.4 miles)

On a cool July morning in 2010, my son Henry and I left our house in Glenburn, Maine before 5 a.m. I promised Henry donuts for breakfast. We went into Tim Horton's in Old Town, after passing two closed Dunkin Donuts, and walked up to the counter.

“We want to get a couple of donuts,” I said to the two guys behind the counter.

“We don't have any yet.”

Henry and I looked at each other. Panic began to creep into Henry's expression. It's not wise to come between an eight year old and his donuts.

“None?” He asked.

“We have muffins.”

Henry leaned in toward me and whispered: “I don't want a muffin. I want jelly donuts.”

We slouched back to the car and drove north, hungry, planning to stop in Lincoln. Every town in Maine with more than three people has at least one Dunkin Donuts. Every town except Lincoln. I suggested we drive through McDonald's—something the kids always want to do that violates my personal ethic. No, Henry wanted donuts or nothing. We ended up at the Irving gas station.

As we drove north through Mattawamkeag, Henry lolled in the backseat deep in a donut-induced sugar coma, flecks of glazing and crumbs on his face and shirt.

We were heading to Baxter State Park—home of Mount Katahdin—for Henry's first backpacking trip. He'd been day hiking his whole life. At first in a Kelty carrier, then joey-like, venturing out of his pouch for longer and longer periods, until the carrier became the home base for his sister Emma. Henry first climbed 1981 foot Borestone Mountain, our family's favorite hike, under his own steam at three and a half. The hike is two fairly steep miles up to a rocky dome overlooking Maine's central highlands.

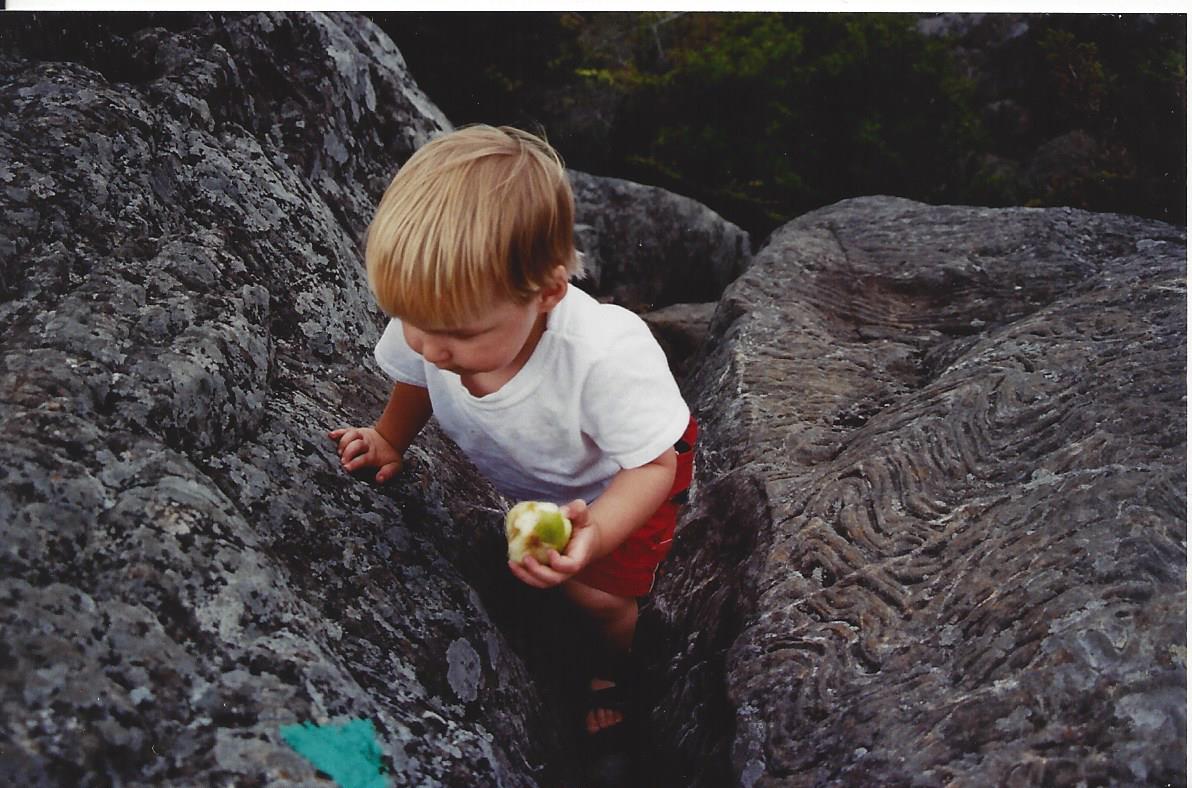

The first mile of the hike climbs steadily through an open spruce forest. There is a respite in the middle where the trail skirts around a pond, then climbs more steeply to the summit. The last bit is more rock climbing than hiking. Henry loved it, but hated my hovering over him as he made his way up the steep rock. For years I had a photo on my desk of Henry near the summit, one hand gripping the rock as he climbed, in the other hand a half-eaten Granny Smith apple.

Now I looked in the rearview mirror at Henry. He slouched in the backseat, watching the befogged Penobscot River come in and out of view behind tumbledown houses with rusting cars and shiny ATVs in their dooryards.

On a crisp October day the year before, while climbing Mt. Megunticook in the Camden Hills, I realized just how far I would go to get Henry's cooperation. My wife Ann led the way, carrying Emma in the Kelty. I hiked in the middle; Henry brought up the rear.

“Why do we have to hike. It's too hard.” The whine in Henry's seven-year-old voice set my teeth on edge.

I stopped and turned, looking back down the wide, leaf-covered trail. The morning light caromed off the multi-colored leaves. The woods seemed to glow yellow and orange. “Why don't you see how many different colors of leaves you can find while you walk?”

“Can we go back? I'm bored.”

I gritted my teeth and looked up the trail where Ann waited, Emma leaned out to her right so she could watch me. I took a deep breath and threw years of crunchy parenting out the window: “Henry. I'll make you a deal. If you stop complaining, when we get to the top you can have an entire bag of marshmallows.” Ann and I try to feed our kids healthy foods and stay away from processed junk. Our backyard is more vegetable garden and chicken pen than grass.

“Really?”

“Really. You might even enjoy the hike. Look at the colors.” Emma waved the handful of maple leaves she and Ann had picked up. Without comment Henry started walking again, slowly at first then with more gusto. The rest of the climb passed in a swirl of leaves and laughter.

I'm glad to say that after eating four marshmallows, Henry gave the bag back to me. Still, if you'd asked me ten years ago if I'd be likely to have a bag of marshmallows in my pack on a hike, I would have laughed at you. Twizzlers and Snickers had become an integral part of our family hikes. We cravenly bribe Henry and Emma to go on hikes without complaining.

And now Henry sat in the back seat of the car in a sugar coma from eating several donuts and part of a bear claw.

Even after chasing all over for donuts, we pulled into the muddy wallow next to the Tote Road across from the trailhead before 8. We were in such a rush to get started that we forgot to take a picture. We were going to hike a loop of about 27 mostly flat miles in three days. Both nights we'd sleep in an Adirondack-style lean-to, a three-sided log structure with a metal roof and a wood floor for sleeping. Baxter rules guaranteed us the whole lean-to each night. Few people day hiked where we were heading; we would likely have the whole place to ourselves.

For years, I dreamed about backpacking from one end of Baxter State Park to the other: exploring the lakes, woods, and mountains of Maine's crown jewel in one overwhelming two-week hike. But between work and family, I never carved out the needed time. Instead of actually doing the hike, I spent free moments with one of my maps of the park and Stephen Clark's guidebook, tracing possible routes through Baxter from the remote far north to the Penobscot River. I also planned routes through and around Grafton Notch in Western Maine, the Wild River Wilderness in the White Mountain National Forest, Acadia National Park, Moosehead Lake, and the Debsconeag Wilderness south of Baxter State Park. On my maps and in my dreams, I visited all the blank spots.

Henry and I walked across the Tote Road to the Wadleigh Brook Trailhead near the north end of Baxter State Park. If this trip worked out, my dream of hiking from one end of Baxter to the other might change. Maybe Henry and I could do it together in kid-sized pieces. Henry stood on the trail, his thumbs tucked under the shoulder straps of his pack. He was only eight. Could he meet the challenges that lay ahead?

“You ready?” He asked.

“Yeah, you lead.” Henry turned and walked into the woods. He wore black basketball shorts that hung down below his knees and a black athletic shirt with a gray stripe down each side. Like me he wore running shoes. He carried an old daypack of mine—the same pack I wore on my first backpacking trip thirty years ago. Even though it only contained his sleeping bag and a change of clothes, it shifted his center of gravity dangerously backward. He still walked with an eager grace, too young to swagger.

His blond hair poked out around his gray and blue Glenburn Little League hat which Henry pulled down low, drawing attention to his ears and leaving his face in shadow. His cheeks were still rounded with baby fat, but the rest of him had thinned out.

The first mile of hiking pretty well soaked us. The trail wound through low, muddy areas overgrown with drooping ferns wet from the night’s rain. In several places the ferns grew as tall as Henry. Overhead, a steady breeze tugged topiary clouds across the sky. Moose tracks and piles of scat in the trail far outnumbered foot prints. In one muddy spot, we saw a very clear bear track as big as Henry’s size-six footprint.

Henry squatted down in the trail, hovering over the spoor. He measured it with his hands. “It's big.”

I thought the idea of bears might scare him.

“I've never seen a bear.” Henry looked up at me. “Do you think we might? Cos that would be really cool.”

Henry hiked in front of me, so he could set the pace. He often caught his foot on roots or rocks in the trail, causing him to stumble. He fell five or six times. After one trip that left him sprawled out across a lichen-covered granite rise, I gave him a hand up.

“You okay?”

“Yeah.”

“You want to stop for a rest or a snack?”

“No. Let's keep going. I want to get to the lean-to where we're eating lunch.”

Henry turned and crosses the rock that had tripped him up. He took big, confident strides. One hand held a Twizzler to his mouth that he nibbled like a rabbit. He held the other hand away from his side palm forward to brush through the ferns as he walked. Occasionally, he patted the rough bark of a maple or the cankered trunk of a beech. Henry looked like he belonged on this trail.

I didn’t anticipate his focus on moving toward the next goal. Early in the day, he fixated on lunch at the Wadleigh Bog lean-to, asking for descriptions of the lean-to and how far it was.

We hiked through maple forest where shards of light kaleidoscoped across every surface. Where the ground was rockier, we crossed dry patches of evergreens. To our left, the ground dropped away to the alder-choked course of Wadleigh Stream. The monotony of putting one foot in front of the other over and over eroded Henry's enthusiasm.

“The lean-to must be around the next bend,” Henry informed me for the third or fourth time. The stream course widened into an open wetland to our left through the screen of trees—a wide sunny expanse of alders and cattails alive with buzzing mosquitoes and croaking frogs. In Henry's mind that meant we must have hiked almost to the lean-to.

“Well, I don't know. We haven't been here before. Let's just enjoy walking.” Optimistic parental platitudes poured out of me. “We'll get there when we do.” It sure seemed to me that the lean-to should be around the next bend. I'm pretty fair judge of distance, and it felt like we'd walked long enough.

“Maybe we'll see a moose.” As a way to get Henry to stop and rest, I scanned the bog for moose. Out in the bog, nothing moved beneath the sun's glare.

A few minutes later: “Is the lean-to around the next bend?” Henry asked again. So far his pace hadn't flagged.

“I don't know. You wanna stop now?”

“No.”

“Wanna drink?”

“This isn't fair. We should be there. The lean-to will be right up ahead.”

But it wasn't. Ten minutes later we got a good view of Wadleigh Bog from a low, spruce covered ridge that dropped down to the wetland. I scanned the edge of the bog for the lean-to in vain. “It's not fair. We've been walking so long. The lean-to doesn't exist!” He sobbed. His arms hung limp from slumped shoulders.

The deterioration of Henry's mood didn't surprise me. He had hiked so hard all morning, barely stopping to snack or drink despite my prodding. I got the map out of my pocket and studied it. I felt bad for Henry. He wasn't acting like a backpacker but like an eight-year-old.

I stood on the trail where the softwoods smelled like Christmas, and stared at the map of Baxter State Park from Stephen Clark's guidebook. We should have already passed the lean-to. Or it should have been right in front of us. Henry looked expectantly at me, blue Nalgene water bottle held loosely in his right hand.

“Where is it?”

“Let's just walk a little more.” I didn't know what to tell Henry. One of my favorite maps seemed to have failed me.

A few minutes later I finally ordered a stop at a nondescript, but sunny, spot on the trail. The young fir and spruce trees grew in a thick green wall, blocking our view of the bog. A few taller trees rose above them. Some years ago a cedar had fallen in the trail and broken apart, leaving the trail carpeted with red chunks of soft, fragrant wood. A hundred feet beyond where we sat the trail disappeared into a tangle of roots, mud, and alders along a slow stream that fed the bog. I breathed in cedar and mud.

Henry collapsed on the ground, letting his pack fall into the trees behind him. I took my pack off and got our food bag out and handed him two Pop Tarts.

“I can't walk any more. Dad, I'm too young to backpack.” He brushed away the last of his tears.

I sat on a fallen tree. “Nah, you're plenty big. You walked farther this morning than you've ever walked on a day hike. You'll be fine.”

“I don't feel like a real backpacker,” Henry looked down at the Pop Tart in his hand. He meant that he didn't think backpackers cried or got discouraged.

“You look like one.”

While eating an apple and sausage, I got out Stephen Clark’s guidebook. Even though his map showed a lean-to along this section, the trail description in the book made no mention of it. The plan had been to walk four and a half miles before lunch, but since we never came to the lean-to—which in fact didn't exist—we ended up walking more like six miles.

“Want some apple?” I asked Henry. In response he held up his Pop Tart.

Henry was a people-pleaser. He worried about disappointing his teachers or letting down his friends. At basketball practice he stood with rapt attention, listening to his coach while his teammates fidgeted and goofed around. Then he came home and pushed back against my parenting. When I asked him to hang his coat up or put away his backpack, he'd just stare blankly at me and walk away. It pleased me to see him try to take care of himself for a change, but wish he'd do it more with others and less with me.

“Want some sausage?” He just looked at me. Maybe, all that bribery on day hikes over the years hadn't been such a good idea. Sometimes it's hard to tell the difference between expediency and creative parenting.

“Guess what,” I began. “There isn't a Wadleigh Bog lean-to. The best I can figure, we walked at least six miles. That means we only have two and half to go.”

Henry shoved half a Pop Tart in his mouth, and started to pack his stuff. “Let's go.”

“Henry. Sit. Ten minutes ago you said you couldn't walk any more.” But he couldn't sit. A new goal had risen before him: the end of the day. He paced around, waiting for me to pack up our lunch stuff. Watching him, I saw myself. I have never been able to sit and relax for very long; always antsy to hike more miles.